I was one of the first female train operators at BART. This is my story.

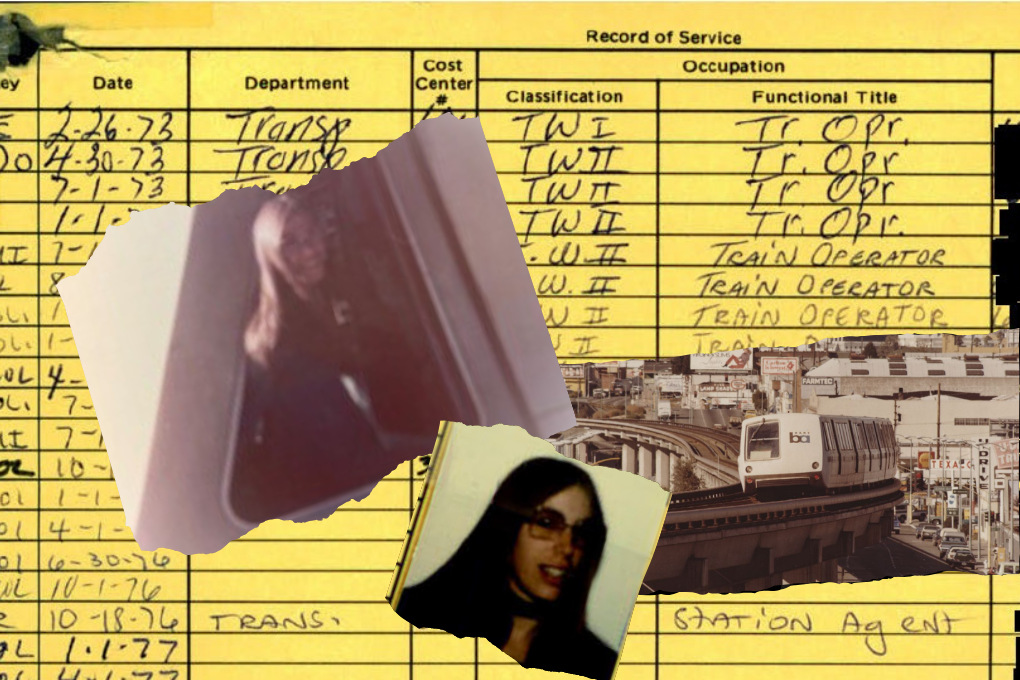

Susan Lynch's BART employee file from the 1970s, overlaid with a photo of her in a BART train cab (left) and the polaroid attached to the file (right).

A note from BART Communications:

Susan Lynch was one of just a handful of female train operators working at BART in 1973, one year after the system opened for service. After graduating from Mills College, Susan decided to apply for the role because “it sounded super sci-fi and a great job for someone who loved to travel."

Being a woman in the workforce in the 1970s was challenging everywhere, and in her years working at BART, Susan said she was no stranger to adversity because of her gender.

Susan said the experience instilled in her compassion “for all women working in non-traditional jobs.”

“Being a woman in the workforce is much more acceptable now than it was in 1972, but there’s certainly still a glass ceiling and discrimination in many workplaces, and I can empathize with all people facing that discrimination,” she said.

After years working in the film industry and administration, Susan, now retired and living in Venice Beach, said she’ll never forget her experiences as a BART train operator and later as a station agent.

Reflecting on the experience five decades later during Women's History Month, she said, “I am proud of myself for going after something I wanted, and I really believe that the future of our society is tied to the future of mass transit. I remember when I rode BART all the time what a feeling of freedom I felt – to be able to travel so far, in comfort and in style.”

Below, Susan shares some of her BART memories – the triumphs and the challenges – in her own words.

I was one of the first female train operators at BART. This is my story.

By Susan Lynch

I spent my junior year in college abroad in Stockholm, Sweden. The highlight of that six-month period, in addition to playing in a rock band (and learning how to smoke hash mixed with tobacco in a chillum pipe) was my growing fascination with trains. I lived in a suburb of Stockholm in a small studio apartment, which I rented for sixty dollars a month. I experienced the joys of commuting by Tunnelbana, or the subway. My twenty-minute excursion each way was mind-boggling because about half of the subway drivers were women! Who would have imagined that in 1970, women could be allowed to drive trains!

When I returned home, I finished my education at Mills College, then a women’s college, where I had learned that I had as much right to a meaningful job as a man did. I was floundering, working mindlessly as a waitress at the St. Francis Hotel in Downtown San Francisco.

Then I managed to join a film-acting workshop taught by a group of socialist filmmakers. They were part of a political collective called “Cine Manifest.” I was already politically sensitized – a card-carrying protester against the war in Vietnam and a bra-burning feminist. But after joining the group I was more determined not to stay in a dead-end, “ok-for-chicks” job. I totally embraced “workers of the world unite” and wanted to impress my sexy comrades.

I’d been reading about the new Bay Area Rapid Transit System that was building a railway in the Bay Area. I remembered how joyful I had felt in Sweden with the female subway drivers, so in 1973, I applied for a job as a train operator. Part of my desire to drive a train was my genuine love of trains and travel, but a much greater stimulus was to rebel against my parents and my upper middle-class upbringing. I wanted to smash my good girl mold and remake myself into Rosie the Riveter!

I submitted my application to be a train operator, and lo and behold, they offered me the position! Most of the classes before ours had been made up of former bus and train drivers – union members. Female train operators like myself were few and far between, and in 1973, I was one of the first women in the role.

The women train operators had a strong sense of comradery and offered each other support because we were combating hostility and harassment from our former teamster colleagues. Their point was we could do the job, but no way should we be paid the same. After all, we weren’t supporting families.

The physical requirements during our training were quite stringent. We needed very good upper body strength. Part of the training was to lie on the floor of the train car, hang out the open door over the edge, and push down on a t-mechanism to manually unlock all the doors in the car in case of emergency. It was touch and go, but we all passed and were full-fledged train operators.

During training, I walked under the San Francisco Bay through the Transbay Tube. The tunnel wasn’t yet completed, so we were shown how it was structured to be highly pliable during an earthquake. I must say, I had to overcome some trepidation and claustrophobia going down there, but once there I felt very safe. I was relieved that I’d be safer during an earthquake on a train in the tunnel than above ground.

After graduating from training, and because I was the lowest on the seniority ladder, one of my few options was a night shift out of Hayward Station as a test driver. Since I still wanted to go to my film-acting workshop, I chose a shift where I worked from 8 p.m. ‘til 4 a.m. with Mondays and Tuesdays off.

I loved being a test driver in 1973, mainly because I was in control. We did reliability testing – driving the trains back and forth for hours on end, making sure that they wouldn’t fail. I would work with the engineers who were designing the cars, which allowed me to use my brain and my problem-solving abilities.

My car at the time was a Citroen DS19 and driving home at 4am on the empty freeway was exhilarating. One night there was a car tailing me. This often happened – a weirdo would notice that an attractive young woman was driving alone in the middle of the night and tail me. I was trying to avoid this guy, driving eighty, when the cherry lit up and the cop pulled me over. When I showed him my ID, I also pulled out my BART ID. I told him I’d been driving trains at eighty miles per hour all night, and it was a challenge to slow down. He asked me for the number of the HR department so his daughter could apply for a job driving trains, tipped his hat, and let me go. I had clearly chosen the right profession.

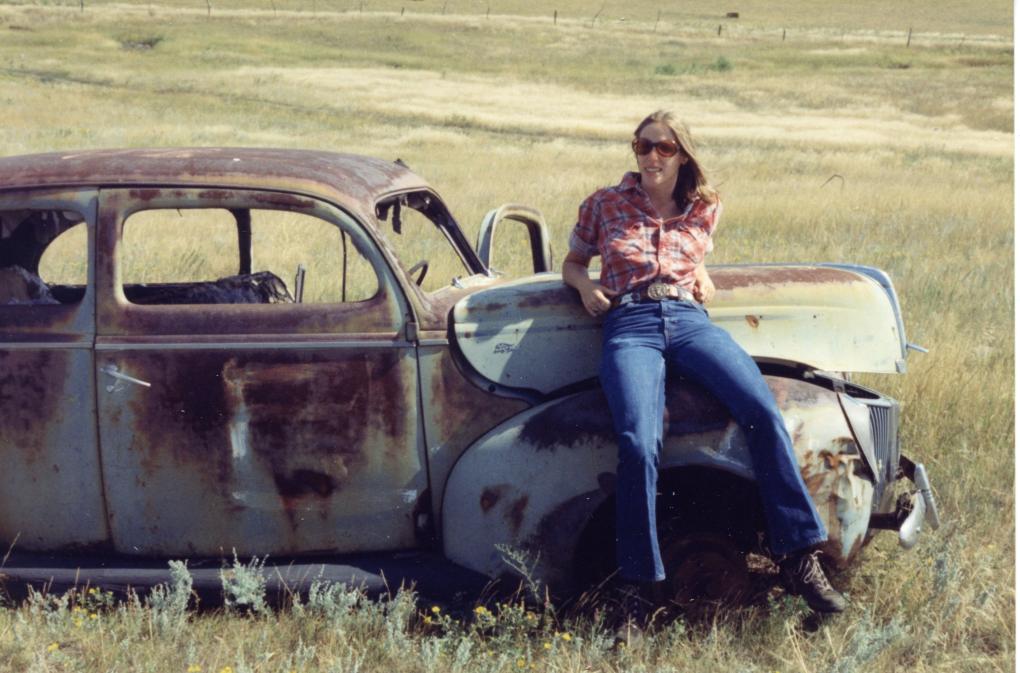

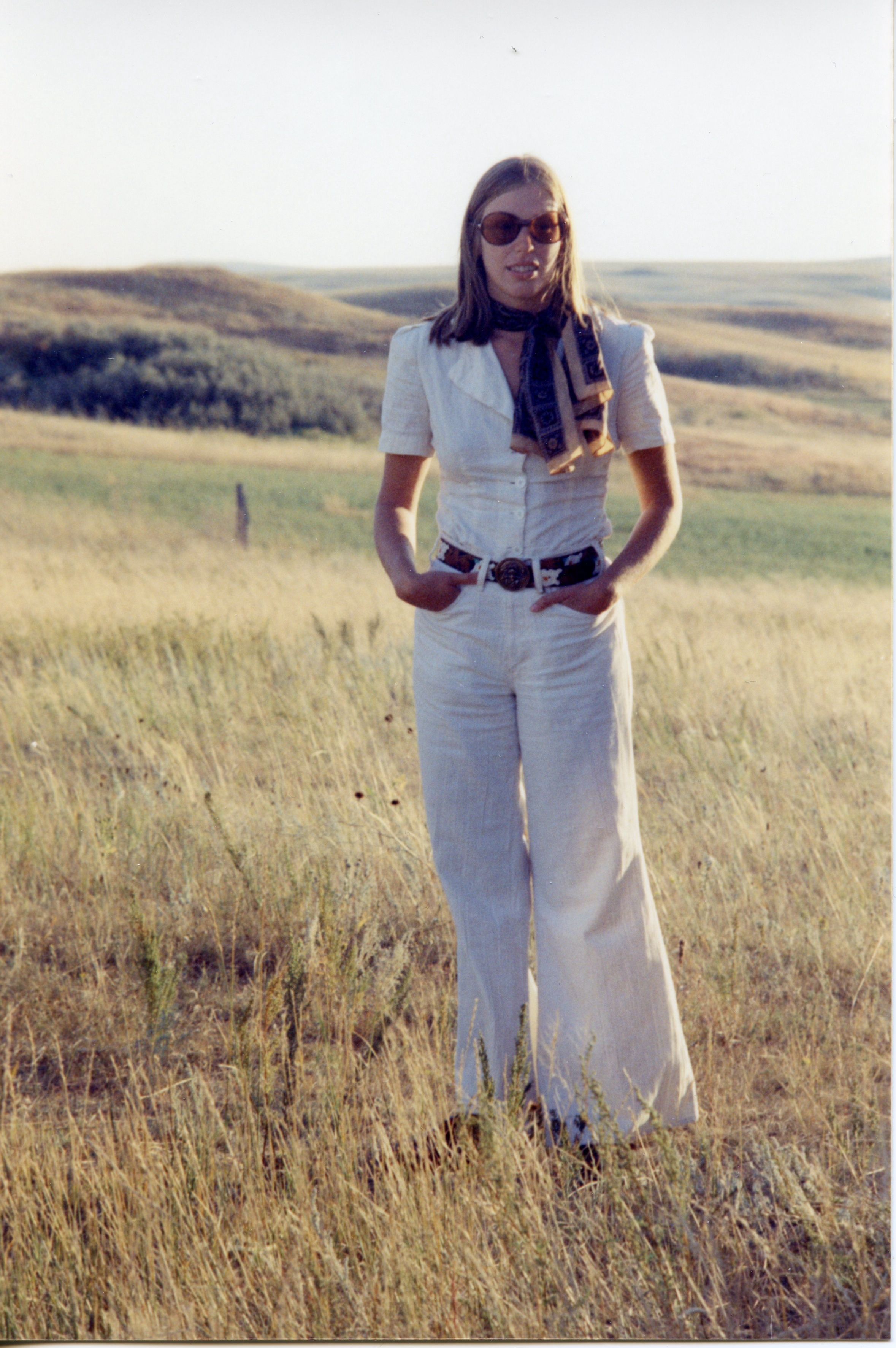

Susan Lynch pictured in the 1970s.

My male coworkers’ response to me was very hostile. Because of this, I felt I had to be just like one of the guys, so my personality took a dramatic shift, and I came to work in a flannel shirt, distressed jeans, army boots, and a leather bomber jacket. My mouth became so filthy that every other word was “f---- s---.”

It wasn’t me, but at least it kept the boys from coming onto me. I felt intimidated when they verbally attacked me, and my newfound bravado made me feel safer.

As my seniority increased, I got a day shift and starting work at 7am. Often, as I leaned out of the window in the station watching that the doors didn’t squash anyone, a man would come up to me and say, “Sure a little lady like you can handle a big train like this?” It was aggravating and mind-numbing.

After a few years in the job, I decided it was time to hang up my train operator hat. My great experiment in being a foul-mouthed worker had failed, but the failure allowed time to drive to research the film I wrote and starred in, Northern Lights. But that’s another story.

After my star turn, I realized I missed the excitement of BART – the hustle and bustle of the stations, the trains that whooshed through the tube at 80 miles per hour, and most of all, my feminist comrades. So, in 1976, I decided to apply gain – this time for the role of station agent, most of whom were women back then. It was my final farewell to my days as “one of the guys.”

In the end, my time at BART helped me find my true calling. I learned that I’m very strong and determined, and that I can handle adversity with resilience and, most importantly, a sense of humor.

My message to women still fighting for equal treatment in the workplace is this: It’s hard, but certainly worth fighting for. Many of us were pioneers that helped the road run a bit smoother for future generations. And I want women today to know that the feeling of pride and self-determination that will come out of the endeavor will be worth everything.

A recent picture of Susan Lynch with the D&SNG No. 476 steam locomotive.