Search Results

BART hosting community celebration of newly modernized El Cerrito del Norte Station on 9/10/21

The public is invited to join BART in celebrating the completion of the El Cerrito del Norte Station modernization project and tour the new features and art. The event on September 10th will include: Food trucks ( LoadedChickn and Shaw's Texas Style BBQ) Music ( The Road Runners band) Giveaways Meet the

Podcast: The future is now; the journey of the Fleet of the Future from blueprint to backbone of BART’s daily service

BART’s base train schedule now consists of all new Fleet of the Future trains, a major milestone for a project that’s been more than a decade in the making. On our latest edition of “Hidden Tracks: Stories From BART,” Project Manager John Garnham reveals how fast the new cars speed along BART’s test track, explains why the process of building the outer shell is a bit like using a classic DIY toy and other insider nuggets.

Transcript below:

JIM ALLISON: Welcome to the latest edition of “Hidden Tracks: Stories from BART”, I'm Jim Allison. On September 11, 2023, BART began to run only new cars for the base schedule, truly a history making milestone for BART. All 55 trains in service are made up of new cars what we call the Fleet of the Future. So, it's my pleasure today to speak with John Garnham, the Group Manager of the Rail Vehicle Capital Program. John, I think that's your official title but I like to think of you as the honcho of the Fleet of the Future. How long have you worked on the program to bring these news cars to BART?

JOHN GARNHAM: Well, we started this program in 2012 so, it's been 11 years in development.

ALLISON: So, 11 years in now, what's the latest on the delivery schedule, how many cars do we have in service, how many do we have on our facilities and how many more can we expect?

GARNHAM: So, we have 611 in service, and we have 627 onsite. They come in every day so it's hard to keep up with it. They've been given us 20 a month. So pretty much one a day, or five a week is usually what they deliver over to us and then we put into service.

ALLISON: And I remember back a couple years ago you had told the board that the delivery schedule would ramp up and in fact is has now.

GARNHAM: It has. They have some issues with suppliers, but they've managed it very well. So, to make 20 a month for the last six months is pretty, pretty remarkable.

ALLISON: Okay, so describe the journey of a car when you have, a blueprint, how does it end up getting here on our facilities, what is the process, where is it built?

GARNHAM: What actually starts with this developing the specification and that started in 2008 or somewhere around in that timeframe. But then the supplier is awarded the contract, and then it's a three or four year design effort.

We spent a lot of time in Montreal, and they spent a lot of time her. Understand our facilities doing testing, testing different bases. The car body, for example. There was this collapsible unit that we had to test we tested it first and then we put it onto the end of a car and we tested that and then we put a whole car body together and we crashed that just to make sure that we knew where the energy went during a crash. So, there's a series of build ups you start with a with a drawing and then you have a part and then you have an assembly and then you have a car. And from there I went down to Sahagun, Mexico. That's where they build the shell. They have a very large facility down there and they build the shell complete. They ship it to Plattsburgh (New York) and Plattsburgh does the final assembly. They put in all the air conditioning, the propulsion. They build the trucks there, the wheel assemblies, we call them trucks, their power, they have motors on them.

ALLISON: The trucks are axles with the wheels.

GARNHAM: That's correct. They're a big structure on each end of the car with two axles and two motors and two sets of brakes. You put those on and then they put them on a truck and they ship them to our test track where the final testing is done.

ALLISON: Okay, so you mentioned in Mexico, they build the shell, the shells are aluminum. And I understand it's kind of an interesting process to take that aluminum which is a metal that we're all familiar with and make it into the outside of a BART car. How's that work?

GARNHAM: Actually, it's an aluminum extrusions. So, an extrusion is like if you had kids you have Playdough and you put it in this thing and you push the handle down in this little tube come out, that’s an extrusion except they do it with metal but the same kind of process. They force it through a dye, and they have the 70-foot extrusions that they weld together for the floor. And they do the same for the ceiling. Then they actually build the floor up in the ceiling up, before they put it together and they do the same with the sidewalls. They weld those all up and build them together. So, they put in insulation, they put wiring, they put lights on, everything's together and then they take it to this area where they call it the splice station and they put the floor down and they put the sidewalls down and they put the roof on top. They have a special bolt called a Huck bolt. It's a rivet but it explodes at a certain force, so you know what the forces are.

ALLISON: What’s it called?

GARNHAM: It’s called a Huck bolt. It's a type of rivet, basically it's an engineered rivet. So, you want it a specific length and it holds a specific pressure. So, they Huck the car together and then they bend it send it down the line where they put the windows in. They do a water test. They put some end cabinets in and some additional wiring and then they put the doors on, and then they ship it over for final assembly.

ALLISON: They Huck it together, that's a good verb. So, you have the process finished in Mexico how does it get to Plattsburgh, which is in upstate New York?

GARNHAM: It's trucked. So, I think they have 27 or 28 trucks on the road at any given time. Between taking, they take one a day up to Plattsburgh and they take one a day to BART and then they run that trailer back down to Mexico and fill it up again.

ALLISON: Those are some long-haul truck drivers.

GARNHAM: They get their work.

ALLISON: What happens in Plattsburgh, New York?

GARNHAM: In Plattsburgh, they take all the sub systems like the propulsion everything under the car, the propulsion, the air conditioning, the brake systems, the auxiliary power system, resistors, and they assemble that to the to the vehicle. They wire it up, they connect all the wiring and the connectors. They assemble the trucks, so they put the axles on the frames and the motors are on there and then they assemble the truck to the vehicle. And once they do that, they do another water tests. They do a complete water test to make sure that the equipment doesn't leak and that the interior of the cars, doors etc. doesn't leak because it kind of changes when you get different weights on it.

Then they put it to a full static test. It takes them a couple of days to do but they test every subsystem to make sure it's interfacing with each other.

ALLISON: So, it’s tested all along the way.

GARNHAM: It is, there's quite a few tests.

ALLISON: And you've been to both facilities. Which you like better and why?

GARNHAM: They’re both unique in what they do. So, Sahagun’s impressive in the capabilities they have. The first time you go in there it's kind of a wow factor. But Plattsburgh’s very organized as well. I spent a lot of time up there, particularly in the beginning. I liked them both.

ALLISON: So, tell me what happens when it gets here to BART. You've got a test track at our Hayward Maintenance Complex that was specifically built for the Fleet of the Future. What happens when the car gets here to BART?

GARNHAM: So, there's a ramp at the test track and they back the truck up and they basically drive the vehicle off of the bed of the truck. The truck bed has rails on it so it sits on the rails and it's fastened down to it. So we roll it off the off the ramp, we take it into the inspection pit and then they put on any of the parts that had to come off like collector paddles and copperhead, whatever had to come off to ship it they put it on and then they do a 9001 test. It's a static test again, to make sure everything functions, the lights come on, everything blinks. Everything is working correctly.

Our inspectors go over and do a shipping inspection to make sure there was no damage that everything's on, everything looks good, make sure the covers are on all the equipment. Then Alstom brings it down, well, actually our guys our moving crew brings it down to the lower test track which is powered. And then BART Train Operators do the testing of the 9001. Alstom’s technicians are on board, but our Train Operators drive the train. So, they do a 9002 tests which tests the propulsion and it tests the brakes. So, you have got to get it up to a certain speed like 80 miles an hour and then you hit the brakes and make sure it stops.

ALLISON: You get up to 80 miles an hour on the test track?

GARNHAM: Yes, with single cars and in a small group of cars not with 10 cars but rather with a smaller group. So, they do the brake testing and then they put a train together of two D cars and three E cars. The D cars are the cab control cars and the E cars are just the passenger cars. Then they do a 9004 test which verifies the automatic train control. So, make sure that the automatic train control is working and it stops at the pseudo stations on either end of the test track and it reads the speed codes properly, opens the doors.

ALLISON: How long is the test track?

GARNHAM: It's two miles. It’s a good-sized test track. Yeah.

ALLISON: This is all good stuff for gearheads. Let's talk about some of the things that just the regular passengers notice about the new cars. The most obvious thing of course, is that they have one more set of doors. They have three doors on each side. But what are some of the biggest differences between the new rail cars and the old fleet aside from those doors?

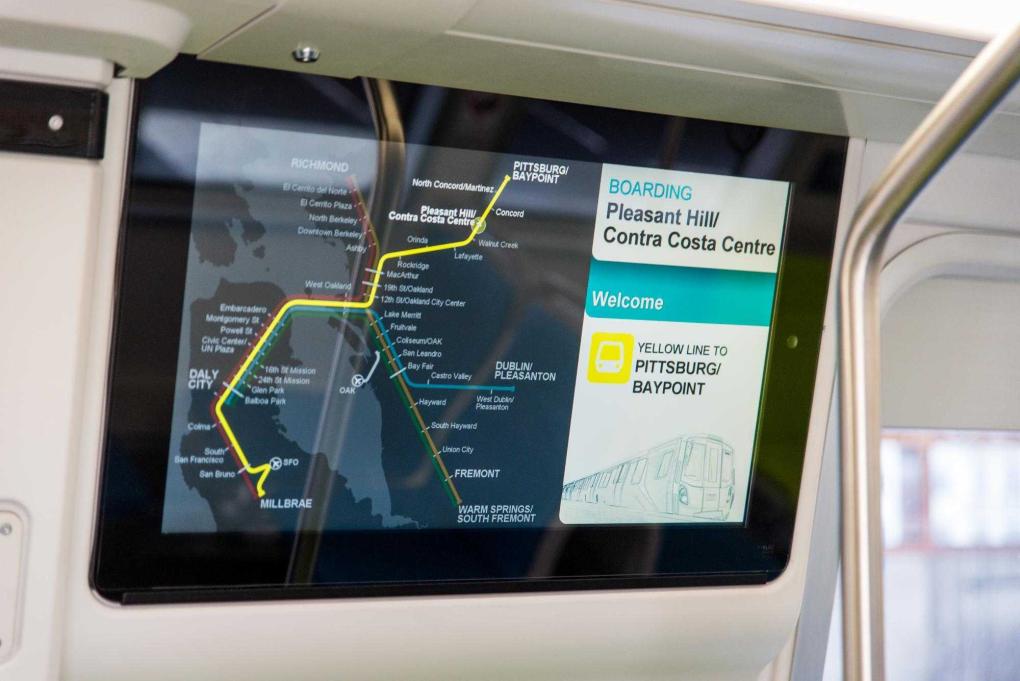

GARNHAM: It's different seating arrangements so it's open. It has the regular commuter seats and then it has the lounge-style seating, but I think with the new maps, where it has a dynamic map. Yeah, it's the customer display monitor and then it's able to put out announcements and do the various messages.

The air conditioning also comes from the ceiling rather than up from the floor. Cold air drops so it feels a little cooler.

ALLISON: So, you're working with physics.

GARNHAM: That was the idea.

ALLISON: So how much has technology changed, rail car technology changed since the early 70s to the cars you're putting in service now? It's got to be pretty profound.

GARNHAM: Yeah, that's a good question. Actually, it's like the old cars were DC motors and these are now AC motors so that's a big difference. You don't have all the brushes and problems with that.

ALLISON: Direct Current, Alternating Current.

GARNHAM: Correct. But the biggest difference is it's all solid state. The old motor boxes when you open them up, there was all these gears that would turn and hit a switch and move it. It's now all solid state you just have a, they’re called IGBTs but that's the mechanism that runs the power and it basically drives the car, you don't have cam operated switches. That's the good thing. The tough part of that is you know, it's tougher to diagnose where the problem is. You can't just open it up and see that there's a connector welded together or something like that. So, if there's a failure you have to take it off and we have these special test units in the component area where you put it on and then you can test it and verify with what the problem is.

ALLISON: Now I remember in the past, you cited some jaw dropping numbers in terms of the length of the cables in these cars, and the number of software changes your team has made as you progressed. You remember those stats off the top of your head?

GARNHAM: You're testing my memory. I think it was 40 miles of cable or something like that. I don't know how many, it's in the hundreds of how many software changes we've done. We continue to do software changes because we're continuing to try and get the reliability up on these cars. So, there's a change going in right now for the train control monitoring system that we're implementing, and it affects the maps and the passenger information system, etc. It's a constant upgrade.

ALLISON: Well, let's be honest, we've had some challenges. Describe why we paused the delivery of the new cars for a time and how your team overcame those challenges.

GARNHAM: Yeah, we did pause. The main issue was reliability. We were retiring the old fleet with a higher reliability number than a new fleet and it just didn't make sense. So, we didn't have the manuals to fix the cars. We didn't have the bench test equipment. All of those were handicapping us to be able to actually work on these cars. We paused, we gave the supplier time to get their arms around the issues, get their arms around the manuals, get the bench test equipment to us, and then we restarted the contract.

ALLISON: So, we talked about the pause in delivery and we've had other starts and stops. Is that a common theme when transit agencies get new fleets of vehicles or is this something that was a particular problem to BART? I would imagine that every rail system has growing pains when they're bringing in a new fleet of rail cars.

GARNHAM: They do. I've been doing rail cars for 40 some years and I don't know project that hasn't had some kind of an issue. If you look at Boston, they are a couple years late on their fleet because they're trying to work out some issues, WMATA (Washington D.C.) had several new fleets and they were late. And then they had some major issues that they had to iron out. The latest New York one was a bit late. Everybody looks at it and says well, it's just a rail, it's just a train, it's pretty easy you should be able to do this but it's got 40 some microprocessors on it. It's got hundreds of pieces of software on it, It's not just a train and each one is different. Each requirement is different. So, in the United States, we don't have a standard product. If you go to Europe, and you go across the different countries that they're trying to standardize all their products, so that once you build it, you just keep putting it out. It's like General Motors or Ford, that first car that they put together. It takes them awhile to engineer it, but then everyone's the same. And the United States was a little bit different. So, every fleet has its unique set of problems.

ALLISON: I think one thing that people may not initially appreciate is the fact that they're entrusting their safety to a transit agency and so safety has got to be paramount, and that that adds to the complexity of delivering these vehicles. Is that correct?

GARNHAM: That's correct. Absolutely, we worked hand in hand with the California Public Utilities Commission. CPUC. We started in 2015 working with them on all the documentation and to verify the safety of it. They had to look at everything, even now before we before we put a train in service we send them to test records, and they verify it and then we put the trains into the service. The original document was probably a five inch binder with paper and records and tests and all the different things that we had to do to put this into service.

ALLISON: And if one is buying an automobile from an automobile manufacturer, you're talking about something to you to use for maybe 10 to 15 years we're going to use these much longer. That's a factor too I would imagine.

GARNHAM: Yeah, the subsystems are a 30-year life. They're designed for 30-year life and the car shells are designed for 40-year life. There are periodic overhauls that you can do on the rehab project, for instance. Those cars the A, B cars, we had them for 50 years, but 30 years in we completely rehabbed them. Replaced everything basically except the car shell on a truck frame.

ALLISON: Is that something that these cars could do?

GARNHAM: I think what we're looking at is many overhauls as we go along, to do that and that's one of the things that we're putting into the manuals where at 12 years you do this, 15 years you do this, at 20 years you do this and it's all about extending the life as long as possible.

ALLISON: Wow, that's interesting. What do you think about what the third generation of BART cars, when these Fleet of the Future ones become the new legacy cars and what's that going to look like?

GARNHAM: They probably won't need rails. It's mind boggling to see the technology in my brief career. You know, from all the cam operated stuff when I started working on it. I was building propulsion for the C cars back in the early 80s for a company called Westinghouse and to see the propulsion that's coming out of their predecessors now it's totally different. It doesn't even look the same.

ALLISON: You mentioned the supplier, and the supplier was originally Bombardier, which successfully was awarded the contract they were competing against Alstom and now Alstom has acquired Bombardier so Alstom is now the supplier. Has that transition affected a project in any way? I know Alstom is a major player obviously in rail vehicles and in the rail industry at large.

GARNHAM: It really hasn't. The project team has stayed the same. I mean, there's constant changes on the project team, but for the overall structure, the consequence of the project team from Bombardier and then to Alstom has remained the same. They've had people leave for various reasons, retirements, or other opportunities, and they had to plug other people in, but for the most part, it's been the same team

ALLISON: And Alstom has people here in the Bay Area working with us.

GARNHAM: They do they do, that team has remained the same. We had one guy retire but they brought another guy in a couple of years ago. So, there's a group on the test track and then they have folks that come in to shops if there's an issue to help our techs troubleshoot it. Our techs do the work but they kind of advise, that's part of the warranty support.

ALLISON: Speaking of the contract, I understand it's coming in 15% under the projected cost. How did you manage that?

GARNHAM: In the very beginning, we spent a lot of time with Bombardier to look at some of their cost drivers. One of the big ones that they had was the original contract was to ship 10 cars a month. And they said early on that they wanted to go to 16 cars a month. So, in the beginning, we did a schedule adjustment to go to 16 cars a month. Obviously worked very well for us. They've had some problems and haven't been able to meet that but when we redid that schedule, it helped on the cost side for us for escalation. There's a clause in the contract that we look at four different indices every year, and we pay them whatever the inflation rate is of those indices. So, that they don't have to try and cost that into their price. It gives everybody an even playing field. Prior to COVID the inflation was very mild. So that helped. But then when we cut a year and some off of the schedule, that cut saved us over $100 million in escalation. That was key to us and that escalation is based on the schedule not on when the cars are delivered. So, we did very well. They ran into problems, and it didn't help them as much as they thought it would but that was one of the cost drivers that they requested and we did so we did a change notice in 2013 or 14 to do that.

ALLISON: How did you cut time on the schedule a year and a half.

GARNHAM: We went from 10 car delivery to 16 car delivery. It got done quicker. They're two years behind, but they're really close to what their original schedule was. So, that was one thing we did. The second thing we did was we tried to bring in as much work as we could inside to our engineers. There are some specialty engineers that we had to get help from that we just didn't have, we don't have the day-to-day knowledge of software, some of the requirements or things like that. You just don't deal with them every day. There were outside folks that we had to bring it to do that but everything else we tried to bring in because our engineers are motivated to fix the problem and solve it. And sometimes the outside folks aren't as motivated to get it done because then they don't have any other work. So, I'm not saying that everybody does that but from my experience if you can do it yourself you really want to get it done.

ALLISON: Well, they’re our cars so our people are really invested in it.

GARNHAM: That’s one thing and then the other thing is our engineers have a lot of experience. We had folks in there with 40 years’ experience, so we gave them a problem they had seen it before. So, it got solved quicker, in my opinion.

ALLISON: Let’s get back to some of the things that these cars improve for riders. We mentioned the three doors on each side, the passenger information. The interior seems roomier. It seems like there's more room for wheelchairs for instance. Data shows these cars are more reliable than the legacy fleet has been in recent years since we resumed delivery, but what's your taken on why that has occurred?

Why are they out there and breaking down less often than the old cars that we've retired?

GARNHAM: Well, part of the contract is there certain reliability milestones that they have to meet. And so that's why we're still doing software changes because although the reliability is improved, they haven't hit the contractual requirements yet. So, there's a very big payment associated with that, which is a motivation for them to meet that and that's a continual process that we're working with them to get to, to where we can pay them that because we want the reliability. When we get to the number we're glad to pay them we just need to we just need to hit that number.

ALLISON: So, the winter of 2022 and 2023 brought the Bay Area's some historic bad weather. We had an unusual number of cars, especially new cars taken out of service. The new cars are more reliable but we did have these cars taken out of service because of something called wheel flats. Tell me what a wheel flat is.

GARNHAM: So, a wheel flat is if the cars are not stopping in the prescribed distance that they have to stop they lock the axels up and it skids to bring it to a stop. When metal skids on metal it creates a little flat spot on the on the round wheel itself. And that's what the flat spots are. So, those have to go into the shop. If they're small, it's not a problem, it's an annoyance. But if they get to be too large, we have to take them in and we cut them off at the wheel. We cut the wheel round again and send it back out.

ALLISON: Why did we have this issue with so many of the new cars as opposed to the old cars?

GARNHAM: That's a great question. The old cars, their train motion ran on stopping at three miles per hour per second. With the new contract, we put in that they had to stop at certain distances. And that's really the right way to do it. You want to make sure it stops within that distance.

ALLISON: Because it's safer.

GARNHAM: It's safer. So, the only way that Alstom could do that was with the train motion that they put in place and instead of one or two cars locking up, the whole train locks up. And so, there's this timer on there. It's called the BPM timer. And basically, it looks at the speed and it says okay, you're over speed, you're over speed, you're over speed, and it gives them like five seconds. And if they don't meet the speed, if they're not coming down to meet the distance, then they lock up all the axles and we ended up getting whatever cars are in that train, we could get flats on them all. So that's why it seems to be more we're working on some issues. We found that there was a couple places in the system where the speeds were changing rapidly. So, we smoothed those out. We kind of blended it so we could, whenever we get the flats we look at where they're at and what time they are and engineers go in and analyze it and if we see that one area, we got six trains flattened then we went in and we would look at those areas and say, oh, yeah, the speed codes. We have charts that we can look at, we can download the car and see the actual charts that have seen and we see and this one is a problem area, we need to blend this out a little bit and reduce the speed a little sooner when it's coming in.

ALLISON: Okay, so that's one design change that kind of braking protocol that's different. I imagine that manufacturing cars for BART, because most people know we have wider tracks than the standard railroad and our cars are unique. What are some of the engineering challenges to design and build a new fleet of cars to run on BART, on the BART system?

GARNHAM: Well, you did a couple of good ones. I mean, obviously the wheel gauges is one. That's why we do the dynamic testing in our test track. Most of the other car builders have normal gauge and car builders have their own test tracks and they do the testing there. Probably the biggest one though is the weight. These cars are 65,000 pounds roughly. An average car of this size would be about 95,000 pounds. If it was made out of steel and our infrastructure just won't handle it because these cars weren't, the infrastructure was designed around the original cars. The original cars were 60,000 pounds. These cars are 65,000 pounds, was a very big effort to get there. Took a lot of work. They had to actually go in and retrofit some of the systems to take some weight out it was not an easy task to do that. The reason these are heavier, we gave we gave them a little extra weight because we had stricter crash worthiness requirements on this car than we did on the legacy fleet. So, as you go along regulations get tighter and tighter and tighter. You can go in and remodel an old house but you couldn't build it to those standards. You'd have to build it to a totally different standard.

ALLISON: We learn as we go along what it takes to be safe. That's a good point. you're taking the existing tracks and the aerial tracks and all of that and you're putting a whole new vehicle on it with all of these new standards that need to be met.

GARNHAM: That's correct.

ALLISON: Wow, that's pretty amazing. So, let’s circle back to the beginning. All the trains and the base schedule our Fleet of the Future. As someone who has so much invested personally and professionally. How's that accomplishment make you feel?

GARNHAM: It makes me feel great. I rode one in today to come here. Always like getting on him, and I kind of look out and see what's going on whenever I’m riding them. But it’s a great feeling. When you’re riding down the road and you point them out to your friends or whatever.

ALLISON: All the sweat and tears worth it.

GARNHAM: It’s a pretty nice feeling.

ALLISON: Well John thanks for joining us and thank you for listening to “Hidden Tracks: Stories from BART.” You can listen to our podcast on SoundCloud, iTunes, Google Play, and of course at our website BART.gov/podcasts.

BART awarded California Humanities arts grant for San Bruno Station exhibit on Japanese American incarceration

BART was awarded a $20,000 grant from California Humanities this month for the renovation of a long-term arts exhibit in San Bruno Station which will examine the local history and impacts of Japanese American incarceration during World War II. The Tanforan Assembly Center Exhibit project, led by Na Omi Judy

BART’s groundbreaking Not One More Girl initiative launching Phase II with focus on community care and new resources for riders

On Friday, June 2, BART and community-based organizational lead partner the Betti Ono Foundation and The Unity Council’s Latina Mentoring & Achievement Program will launch a series of pop-up events for Not One More Girl, a community-driven initiative to address sexual harassment on transit. The launch comes

Local beekeeper makes honey with bees removed from BART property, protecting riders and helping to preserve the critical insect

If you passed by the four-inch notch in the wall on Bailey Road next to BART’s Pittsburg/Bay Point Station, you probably wouldn’t notice a thing. But if you took a closer look – not too close – you’d find a hive of hundreds of buzzing honeybees. The notch in the wall seemed like a keyhole into another world –

BART Board approves project team to build-out new headquarters with priority of small and minority-owned business involvement

The BART Board of Directors, at its June 25th meeting, voted to award a $58 million Progressive Design-Build contract to Turner Construction Company and RIM Architecture to design and build the new BART Headquarters at 2150 Webster Street in Oakland. BART purchased the modest size building on December 10

BART PD makes arrests in fatal shooting in plaza above 24th Street/Mission Station in San Francisco

Updated 4pm, December 28: The BART Police Department working in conjunction with the San Francisco Police Department has arrested two suspects wanted in connection with the December 18th fatal shooting in the street-level plaza above the 24th Street/Mission BART Station in San Francisco. A 19-year-old man and

No BART service between Lafayette & Pleasant Hill Wed. noon-3:30pm, bus bridge set up

In cooperation with the ongoing NTSB investigation, on Wednesday, October 23, 2013 from noon to 3:30 pm, BART will need to operate a bus bridge between Lafayette Station and Pleasant Hill/Contra Costa Centre Station. This means there will be no BART train service between Lafayette, Walnut Creek and Pleasant

BART partners with the San Francisco Asian Women’s Shelter and artist Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya to confront domestic violence on public transit

Let's Talk About Us posters on digital screens at Powell Station The San Francisco Asian Women’s Shelter (AWS) and artist Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya are partnering with BART to launch a new domestic violence prevention campaign, “Let’s Talk About Us,” to reach Bay Area residents and BART riders. The public art