Search Results

Special late-night service added for Beyoncé Renaissance Tour on 8/30/23

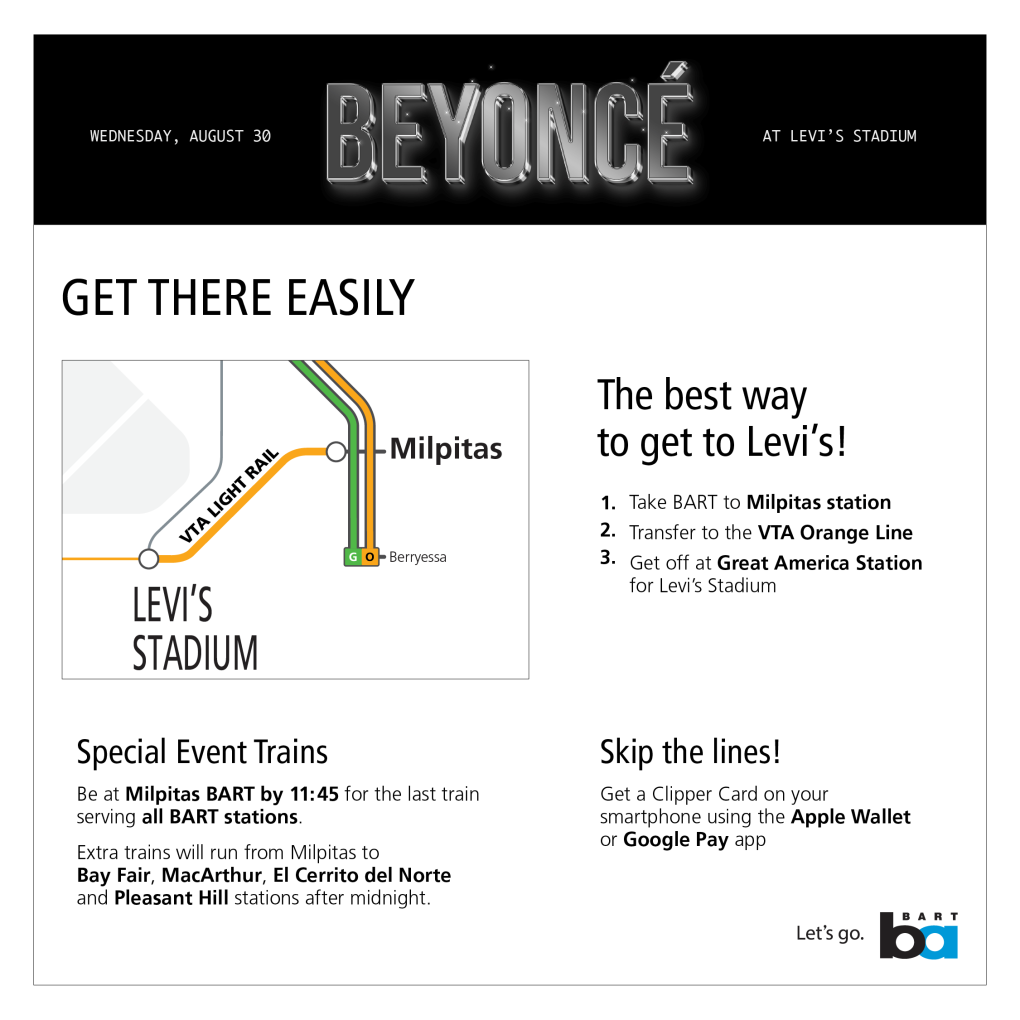

BART will run extra trains and offer special limited service after midnight for the Beyoncé Renaissance World Tour at Levi’s Stadium on Wednesday, August 30, 2023.

Getting to Levi’s Stadium using transit is easy. Fans will transfer from BART at Milpitas Station to VTA’s Orange Line and ride to VTA’s Great America Station, located on the North side of Levi’s Stadium.

BART will have extra security and station staff to help people get around.

What You Need to Know About the Ride Home

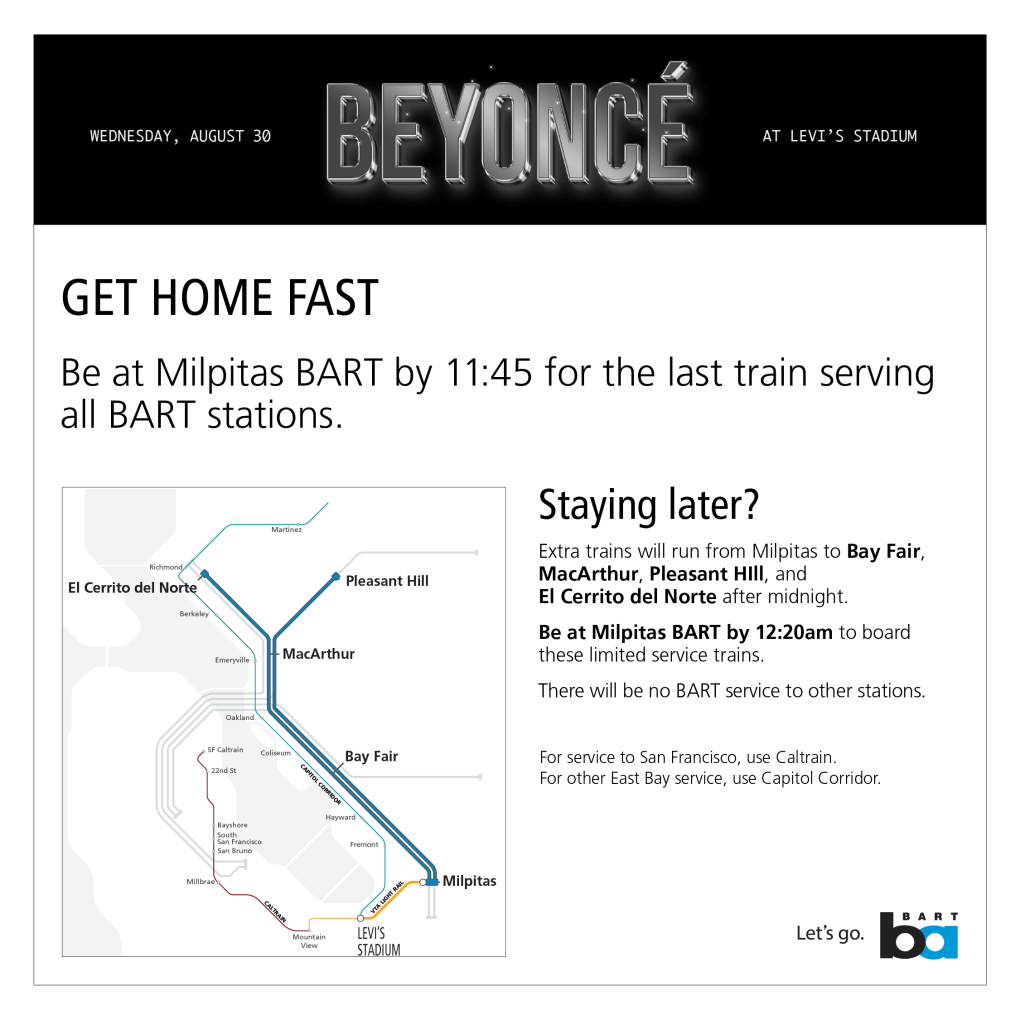

BART will run its normal last train of the evening leaving Milpitas at 11:51pm, making all regular stops. This is the last train that will get you to all BART stations in the system.

BART will run two special event service limited-stop trains that will depart Milpitas Station at around 12:30am serving limited stops after regular BART service ends.

The late-night limited service will pick up riders at Milpitas Station with stops only at the following East Bay stations, the train will skip all other stations without stopping:

- Bay Fair

- MacArthur

- Pleasant Hill

- El Cerrito del Norte

| Station | Special Event Limited Stop Trains |

| Milpitas | Departs at 12:30am and 12:35am |

| Bay Fair | Arrives at 1:06am and 1:11am |

| MacArthur | Arrives at 1:27am and 1:32am |

| El Cerrito del Norte | Arrives at 1:42am |

| Pleasant Hill | Arrives at 1:46am |

These four East Bay stations have large parking lots located near the freeway. Riders who know they want to stay until the very end of the show, should park their cars or arrange pick-up at one of these four stations. Use the timetable above to share your pick-up time.

These special limited stop trains will be labeled “Limited Stop to El Cerrito” and “Limited Stop to Pleasant Hill.”

Other Transit Options

Riders coming from San Francisco should take Caltrain home or ensure they take the 11:51pm BART train home. Caltrain is providing one extra local train from Mountain View to San Francisco 75 minutes after the show ends or when the train is full. BART is not keeping any San Francisco stations open beyond normal closing hours due to the lack of parking lots at SF stations and because Caltrain is providing this special service.

Capitol Corridor is also offering special train service that departs at 11:59pm from their Great America (GAC) station. Capitol Corridor has stops next to BART's Coliseum and Richmond stations.

Other Tips

Parking is free after 3pm at BART stations.

Before you leave home put a Clipper card on your cellphone through either Apple Pay or Google Pay. Clipper is waiving the $3 new-card fee for riders who add either of the mobile options. Please ensure you have sufficient funds for a round trip. Plan at the cost of your trip in advance.

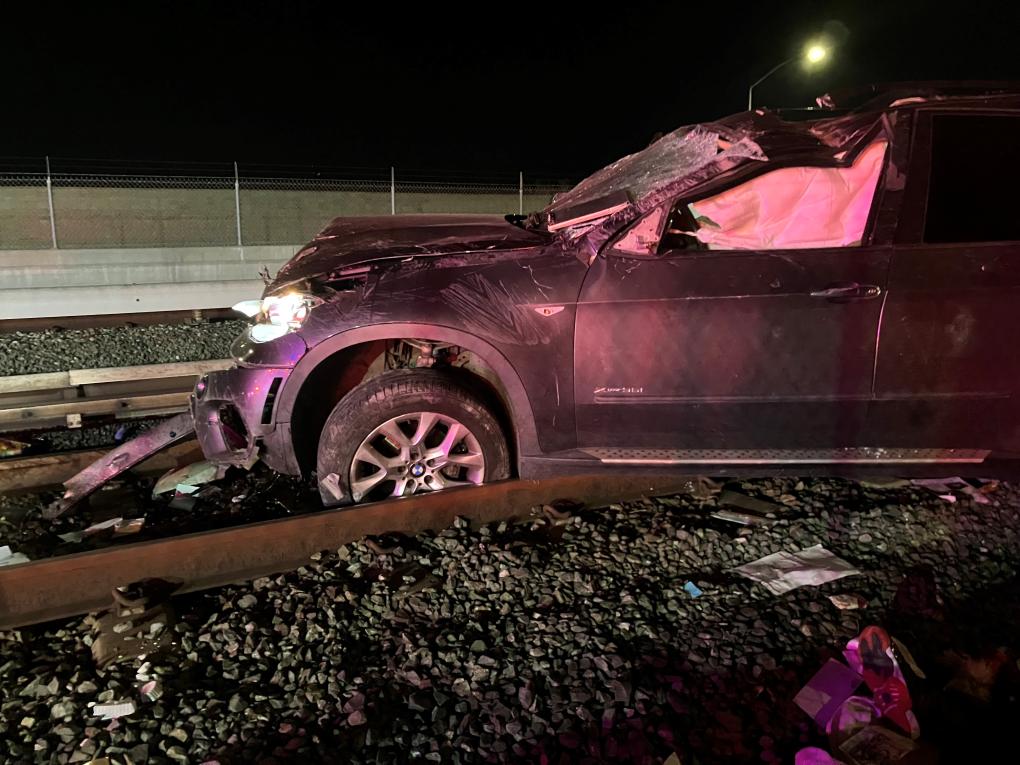

Service restored between Antioch and North Concord following earlier outside vehicle on the trackway

7:40 am UPDATE

Full service restored between Antioch and North Concord/Martinez after vehicle crash.

7:25 am UPDATE

Track inspections underway in anticipation of full service restoration shortly.

7:10 am UPDATE

Vehicle has been lifted from the trackway. And crews are making the repairs to the third rail cover-board and fencing.

We are hoping to open at least one trackway in about 30 minutes.

At around 3:45am a vehicle crashed through barriers and entered the BART trackway about 100 feet south of the Pittsburg/Bay Point BART Station. First responders arrived and reported to BART that the person in the vehicle was deceased.

The vehicle is on the BART trackway blocking both sets of tracks and significant damaged to BART’s third rail and track infrastructure occurred and will need repairs once the car is moved out of the way.

BART will begin morning service with no train service from Antioch to North Concord. Passengers should go to North Concord to catch a BART train.

Antioch Station will not have service to Pittsburg/Bay Point, but the DMU train will take local riders from Antioch to Pittsburg Center.

Bus Info:

As of 5am there is one Tri Delta Transit bus from Antioch to Pittsburg Center to Pittsburg Bay/Point and there are two County Connection buses between Pittsburg/Bay Point and North Concord. We are working with partner bus agencies to get more buses at Antioch and Pittsburg Bay Point to connect East Contra Costa riders to North Concord.

Extra staff are at impacted stations.

The CHP is leading the vehicle investigation and BART crews are on standby to perform track work.

Around the Bay this Weekend: All Aboard Transit Day, special trains for A’s/Ed Sheeran, BARTable ways to observe Hispanic Heritage Month and Rosh Hashanah

Friday, Sept. 15 – We have some huge news to share: This week we’ve seen some of the highest ridership days since the start of the pandemic. On Wednesday, we hit a major milestone – the highest ridership day since spring 2020 with 192,961 rides! Tuesday followed close behind with 192,081 rides. The numbers don’t lie – riders are coming back to BART.

If it’s been a bit since you’ve been aboard, you’ll notice some changes in our system: cleaner trains and stations, additional safety presence walking trains, and a newly reimagined schedule that increases service on weeknights and weekends. Read BART’s new Safe and Clean Plan here.

On Sunday, we greeted another milestone; we said an informal farewell to our legacy trains as our new, Fleet of the Future trains take up the helm for our base schedule (you may see some legacy trains for extra event trains and emergency contingencies). If you didn’t get to a station on Sunday to wave goodbye to the last scheduled legacy train, don’t fret! We’ll hold a proper retirement ceremony in the future, likely next year.

Speaking of celebrations, this weekend marks the start of two holidays: Hispanic Heritage Month (Sept. 15 to Oct. 15) – a celebration of the contributions, histories, and cultures of Hispanic Americans – and Rosh Hashanah (Sept. 15 to 17), the Jewish New Year and start of the High Holy Days. Read BARTable’s articles on local ways to observe the holidays here and here.

The regional celebration of public transportation – Transit Month – is still fast underway as well. To learn more about two exciting events this weekend – All Aboard Transit Day and Meet the BART Anime Mascots – keep scrolling.

We’ve also scheduled special service and event trains for two big events this weekend – the Ed Sheeran concert and the Oakland A’s vs. Padres. Find more info below.

For an in-depth listing of local events, visit the BARTable website. We publish a weekly event roundup, BARTable This Weekend, that highlights happenings around the region as well as cool contests and sweepstakes from our partners.

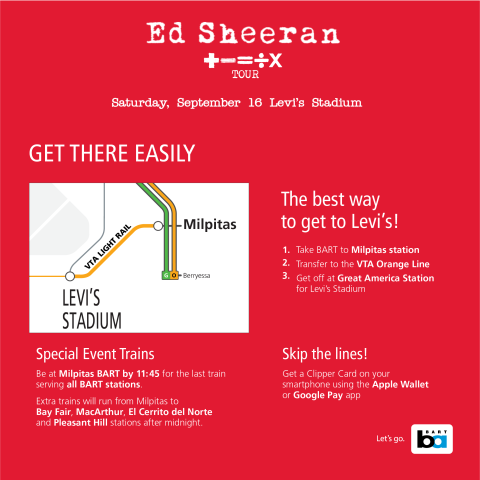

Saturday, Sept. 16: Special late-night service added for Ed Sheeran concert

BART will run extra trains and offer special limited service after midnight for the Ed Sheeran concert at Levi’s Stadium on Saturday, Sept. 16, 2023.

Getting to Levi’s Stadium using transit is easy. Fans will transfer from BART at Milpitas Station to VTA’s Orange Line and ride to VTA’s Great America Station, located on the north side of Levi’s Stadium.

BART will have extra security and station staff to help people get around. Learn what you need to know to get home and read our traveling tips here.

Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, Sept. 15, 16, and 17: Special event trains for Oakland Athletics vs. San Diego Padres at Oakland Coliseum

The Oakland A’s face rivals the San Diego Padres on Friday (6:40pm), Saturday (1:07pm), and Sunday (1:07pm) at the Coliseum. We’re expecting many riders to take BART, so we’ve added special event trains on Friday and Saturday to get fans home from the games.

The Friday game honors Roberto Clemente Day and will include a Latin Music Fireworks Show. The Saturday game will celebrate Latin and Hispanic Heritage Day, and Sunday will honor Make-A-Wish children and families.

Saturday, Sept. 16: All Aboard Transit Day and Meet the BART Anime Mascots at Powell Street

This Saturday, Sept. 16, is All Aboard Transit Day. On this day, we encourage people to take as many trips as their hearts desire to help us beat the September 2022 ridership record, which recorded 500,000 rides across all agencies! We'll total up the ridership numbers and report to the public if we exceed our previous record. Your rides on Saturday can be logged for the Transit Month Ride Contest, too.

Also on Saturday, Sept. 16, is our "Meet the BART Anime Mascots" event at Powell Street Station from 2pm to 6pm. Take photos with the mascots, make buttons with staff, grab a prize from the BART capsule ball machine, and more! Come in cosplay and get a rare BART anime charm. The Link21 outreach team will also table to talk about the project to build a second train crossing connecting Oakland and San Francisco.

Weekend Read: BART Board President and General Manager speak with Manny Yekutiel aboard moving train about future of Bay Area transit

On Friday, Sept. 8, around 65 people gathered in the concourse of 16th Street Mission Station to welcome their weekends aboard a BART train.

They were there to catch an evening train aboard which Manny Yekutiel, the owner of the San Francisco café Manny’s, would host a conversation with BART Board President Janice Li and General Manager Bob Powers about the future of Bay Area public transit. The gathering was a unique opportunity for BART leaders to hear directly from riders, and riders to hear from them. The ethos of the event: Why not hold such a conversation on the very trains in question?

Hear more from Manny, Li, and Powers -- as well as the riders who attended -- here.

Sweepstakes Spotlight: Win Tickets to See Manhattan Transfer at SFJAZZ

With the SFJAZZ season now upon us, enter to win tickets for you and your guest to see Manhattan Transfer on Friday, Sept. 29 at 7:30pm. The Manhattan Transfer has kept the vocalese flame burning brightly for half a century. They will bring the curtain down on a monumental career with these performances at the SFJAZZ Center on Sep 29 and 30, as part of their final tour.

Click here to enter the sweepstakes by Monday, Sept. 18.

Happy Riding this Weekend!

We hope you enjoy your weekend adventures aboard our trains.

Stay in touch by signing up for the BARTable This Weekend newsletter on the BARTable website – your one-stop shop for all things accessible by BART. You can also keep up with BARTable on Facebook and Instagram.

BART General Manager Bob Powers pictured through a train window at West Oakland Station as the train made its way back to the East Bay following a conversation with Manny Yekutiel, BART Board President Janice Li, and Powers on Friday, Sept. 8, 2023. Photo by Evan Dorsky.

Installation work to begin October 28 for Next Generation Fare Gates at Montgomery Station

On October 28, BART will begin the installation Next Generation Fare Gates on the concourse level of Montgomery Station. The installation work will happen in stages so riders can continue to use the remaining current gates while new ones are installed. There will be additional BART staff as well as signage to direct riders to the open gates. Installing each new array is expected to take up to two weeks to complete. BART will eventually replace all seven fare gate arrays at Montgomery. The work is expected to continue into December.

A temporary barrier will be installed to provide a safe workspace for the installation team as well as to protect riders from construction. The work will not impact train service, but riders may experience a few extra minutes wait to pass through the fare gates during peak travel hours.

The latest work comes after BART has successfully installed Next Generation Fare Gates at eight other stations across the system. All 50 BART stations will have new fare gates by the end of 2025. You can learn more about BART’s Next Generation Fare Gate project here. Riders can provide feedback about the new gates at bart.gov/comments.

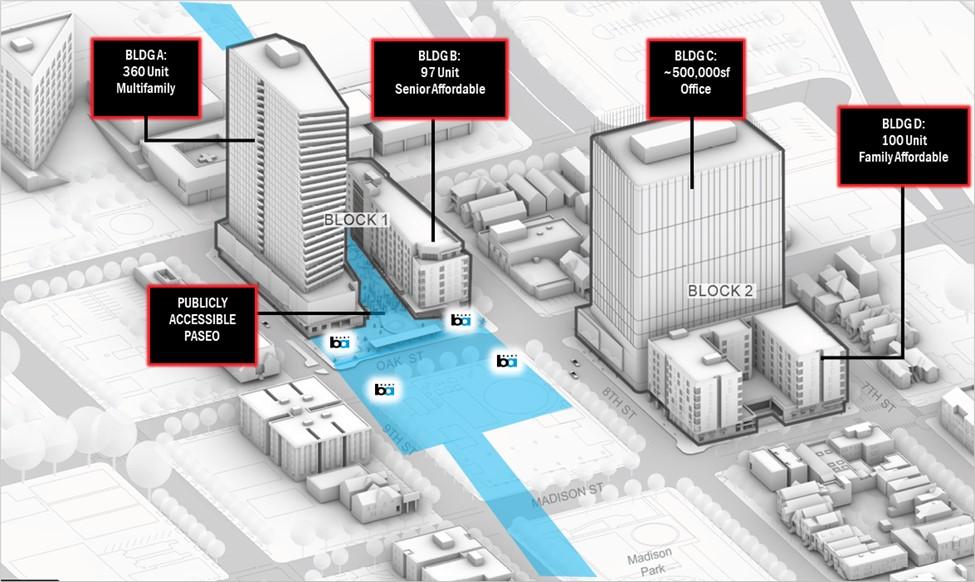

Lake Merritt TOD construction begins in 2024; parking changes start June 1

August 14, 2024 Update

Starting September 16, 2024, our exciting project to develop the land around Lake Merritt Station to include affordable and market-rate housing, offices, and retail space will officially begin. To accommodate this Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) project, the parking lot will be permanently closed starting September 16, 2024. Partial closures will start September 1, and the last day to use the Lake Merritt parking lot is September 15, 2024.

The lot is available for Daily Fee parking on a first-come, first-served basis until September 15. Daily Fee parking payment is required Monday-Friday, 4am-3pm, except on BART holidays. Pay for Daily Fee parking with the BART Official App or remember your stall number and pay inside the station via cash, credit, or debit.

Reserved parking is available at Fruitvale Station, MacArthur Station and many other BART locations with parking.

Starting in 2024, the area around the Lake Merritt BART station will begin to be developed. New affordable and market-rate housing, office, and retail space will be developed over several phases. Phase 1.1 (Bldg. B on the illustration) is currently scheduled to break ground in mid-2024, with the construction of a 97-unit senior affordable housing building on BART’s existing surface parking lot.

To accommodate this Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) project, BART will no longer offer Reserved Parking starting June 1. Daily Fee parking will still be available on a first-come, first-served basis until construction formally begins, when the parking lot will be permanently closed. Customers can check bart.gov/parking for updates on Daily Fee parking availability, as well as signage at the two entrances to the Lake Merritt parking lot.

Lake Merritt Station is easily accessible by bicycle and transit. Reserved parking, including Monthly, is available at Fruitvale Station, MacArthur Station, and many other BART locations with parking.

For more information about the TOD project, visit: bart.gov/about/business/tod/lakemerritt

*This article was originally posted on March 21, 2024

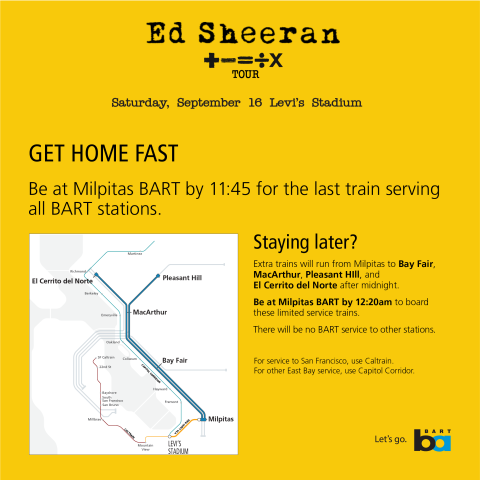

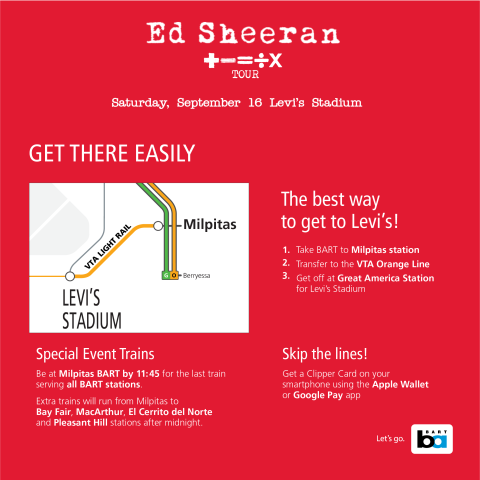

Special late-night service added for Ed Sheeran Concert on 9/16/23

BART will run extra trains and offer special limited service after midnight for the Ed Sheeran concert at Levi’s Stadium on Saturday, September 16, 2023.

Getting to Levi’s Stadium using transit is easy. Fans will transfer from BART at Milpitas Station to VTA’s Orange Line and ride to VTA’s Great America Station, located on the North side of Levi’s Stadium.

BART will have extra security and station staff to help people get around.

What You Need to Know About the Ride Home

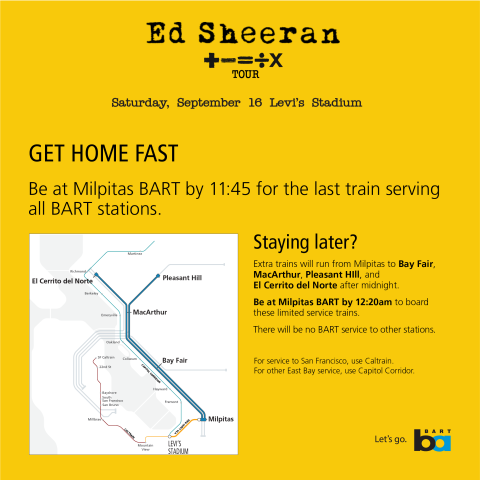

BART will run its normal last train of the evening leaving Milpitas at 11:51pm, making all regular stops. This is the last train that will get you to all BART stations in the system.

BART will run two special event service limited-stop trains that will depart Milpitas Station at around 12:30am serving limited stops after regular BART service ends.

The late-night limited service will pick up riders at Milpitas Station with stops only at the following East Bay stations, the train will skip all other stations without stopping:

- Bay Fair

- MacArthur

- Pleasant Hill

- El Cerrito del Norte

| Station | Special Event Limited Stop Trains |

| Milpitas | Departs at 12:30am and 12:35am |

| Bay Fair | Arrives at 1:06am and 1:11am |

| MacArthur | Arrives at 1:27am and 1:32am |

| El Cerrito del Norte | Arrives at 1:42am |

| Pleasant Hill | Arrives at 1:46am |

These four East Bay stations have large parking lots located near the freeway. Riders who know they want to stay until the very end of the show, should park their cars or arrange pick-up at one of these four stations. Use the timetable above to share your pick-up time.

These special limited stop trains will be labeled “Limited Stop to El Cerrito” and “Limited Stop to Pleasant Hill.”

Other Transit Options

Riders coming from San Francisco should take Caltrain home or ensure they take the 11:51pm BART train home. Caltrain is providing one extra local train from Mountain View to San Francisco 75 minutes after the show ends or when the train is full. BART is not keeping any San Francisco stations open beyond normal closing hours due to the lack of parking lots at SF stations and because Caltrain is providing this special service.

Capitol Corridor is also offering special train service that departs at 11:59pm from their Great America (GAC) station. Capitol Corridor has stops next to BART's Coliseum and Richmond stations.

Other Tips

Parking is free at all BART stations except Milpitas and Berryessa (which are operated by VTA) on Saturday, September 16.

Before you leave home put a Clipper card on your cellphone through either Apple Pay or Google Pay. Clipper is waiving the $3 new-card fee for riders who add either of the mobile options. Please ensure you have sufficient funds for a round trip. Plan at the cost of your trip in advance.

Thank you for joining us at SweaterFest '24!

SweaterFest is back!

On Saturday, Dec. 7, we invite you to rock your BART ugly sweater (and other BART holiday merch) and toast the season for a jubilant community celebration in the plaza at Rockridge Station.

What to expect: Live music, transit-themed crafts (did someone say paper ticket wreaths?), family friendly activities, and photo opps! If you've been collecting stamps for your BART Stamp Passport, bring it to the event to get the new SweaterFest stamp. We'll be handing out a special prize (it's a surprise, but you'll love it!) for those who have five or more stamps in their passports, including the new SweaterFest stamp.

We’ll take a group photo of everyone in their sweaters during the event at 2:30pm.

What: SweaterFest ‘24

When: Saturday, Dec. 7, 1pm to 4pm

Where: Rockridge Station Plaza

More than 6,000 people are proud owners of a BART holiday sweater, and we want to gather as many of you as possible. The event is free and open to everyone – even those of you who don’t own a BART holiday sweater (what gives?!). Got a sweater from a previous year? Wear it!

We will have hundreds of 2024 holiday sweaters available for purchase at the event, along with the suite of additional 2024 BART holiday merch: sweater vests, beanies, scarves. Railgoods will be selling non-holiday BART merch as well, including new Railgoods gift cards, a great option for the hard-to-shop-for people in your life.

You can also preorder holiday merch on Railgoods.com and at checkout, select the option to pick up your items at SweaterFest.

Can’t make it to SweaterFest? You have multiple options to get your hands on BART holiday merch:

Railgoods Holiday Popups (limited inventory)

Wednesday, Nov. 20, 3pm to 6pm, El Cerrito del Norte Station

Saturday, Dec. 7, 1pm to 4pm, Sweaterfest at Rockridge Station

Thursday, Dec. 12, 3pm to 6pm, Dublin/Pleasanton Station

Preorder on Railgoods.com

If you preorder your items on Railgoods.com, at checkout you will have the option to:

- Pick up your order at SweaterFest on Saturday, Dec. 7, 1pm-4pm, at Rockridge Station.

- Ship your order for a fee. Items will begin shipping the week of December 9.

- Pick up your sweater at BART's Customer Services Center at Lake Merritt Station (hours: M-F 8:30am to 4:45pm). If you select this option, you will receive an email when your order is ready. Orders should be available for pickup the week of December 9.

If you preordered a sweater this summer...

If you preordered your holiday merch this summer, you should have either received your order or it will arrive shortly. Those who selected the in-store pickup option during the presale should keep an eye out for an alert that their order is ready for pickup.

You can also win holiday merch from BARTable! Sign up for the BARTable This Week newsletter on bart.gov/bartable to enter holiday sweepstakes and to hear about fun holiday events by BART stations.

Unified schedule changes will improve transit service in the Bay Area

Bay Area transit agencies are syncing schedules in a whole new way with a focus on improving transfers between systems and making schedule changes at the same time.

Most Bay Area transit agencies are rolling out new schedules next week in coordination with each other and are working to align the timing of schedule changes twice each year, once in summer and once in winter. There has been a 250% increase in the number of transit agencies changing their schedule concurrently twice each year, and six of seven major transit providers are syncing their schedule changes at least once a year.

Agencies convened a meeting in March 2024 to share planned changes for mid-August and to look for opportunities to improve transfers. Advancing schedule change alignment is a key priority for Bay Area transit general managers who meet on a weekly basis to make transit more rider-focused and efficient. The major agencies are already working on another iteration of a coordinated schedule change to go into effect in January 2025. These coordinated schedule changes will benefit current transit riders while attracting new riders.

Some key examples of improved coordination from the mid-August schedule changes:

- In the North Bay, a series of coordinated changes between SMART, Golden Gate Transit, and Marin Transit will improve service and connections along the congested Highway 101 corridor.

- The Napa Valley Transportation Authority is making changes to Route 29 from Redwood Park and Ride to the El Cerrito del Norte BART station to enhance the bus-to-train transfer timing. 71% of the trips will now have a 5- to 10-minute transfer time at El Cerrito del Norte, as opposed to 23% with the current schedule. The change will positively impact as many as 16,465 riders annually.

- AC Transit and Golden Gate Transit have improved schedules to be more coordinated at El Cerrito del Norte Station and along Cutting Boulevard west of the BART station. This alignment enhances reliability for riders traveling between Marin and West Contra Costa counties via the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge

- In San Francisco, Muni is making changes to improve regional connections, specifically, the 28 19th Avenue bus schedule serving Daly City BART station is changing to ensure East Bay riders can catch the last BART train to Oakland late at night.

- VTA is making changes to match upcoming BART and Caltrain schedule changes to ensure timed transfers are maintained at various locations across the South Bay and Peninsula.

- SamTrans is improving several bus routes that serve BART stations. One noteworthy change is to bus route 292, serving both Millbrae and SFO BART stations, with frequency (the time between bus arrivals) to be every 20 minutes from 6am- 6pm to match BART’s frequency.

- Both BART and Caltrain will make changes to improve some of the rail transfers at Millbrae Station that will go into effect when Caltrain launches its electric service on September 21. With BART’s schedule change on August 12 and Caltrain’s schedule change on September 21, ~85% of all weekday trains will have a transfer between 5 and 19 minutes at Millbrae Station. On the weekend, ~90% of trains will have a transfer between 5 and 19 minutes, allowing for both systems to be off schedule a bit but still provide a reliable connection. If trains were scheduled with less than a 5-minute wait, delays would frequently break the transfer and result in a longer wait.

Balancing Service Complexities

While all transit agencies are working to improve transfer timing for Bay Area transit riders, several challenges continue to exist making transfer timing difficult:

- A better transfer for one end of a route may create a worse transfer for other areas of the route.

- Adding service to allow frequencies to match each system requires new funding at a time transit agencies are facing significant budget challenges.

- Transfers between BART and Caltrain at Millbrae Station don’t always line up perfectly because Caltrain has four trains per peak hour and two trains per off-peak hour/weekends. BART has three trains per hour at all times. Both systems are also limited in flexibility due to key system timing points elsewhere.

Other Coordinated Improvements to Come

In addition to schedule coordination, Bay Area transit agencies are working together, along with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, on significant regional projects that will transform the rider experience, such as unified transit maps and directional signs and fare integration and affordability programs such as the implementation of free and discounted transfers.

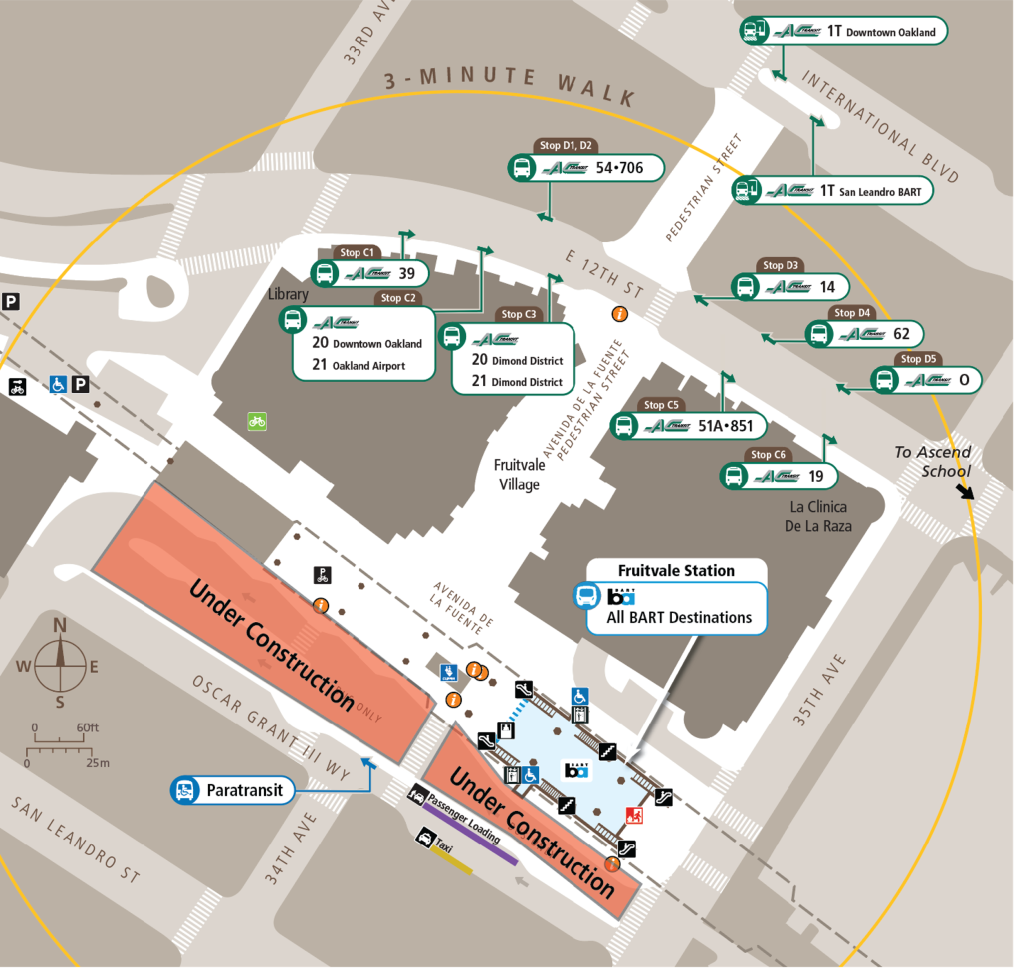

Fruitvale Station: Passenger loading impacts and bus stop changes starting 7/8/2024

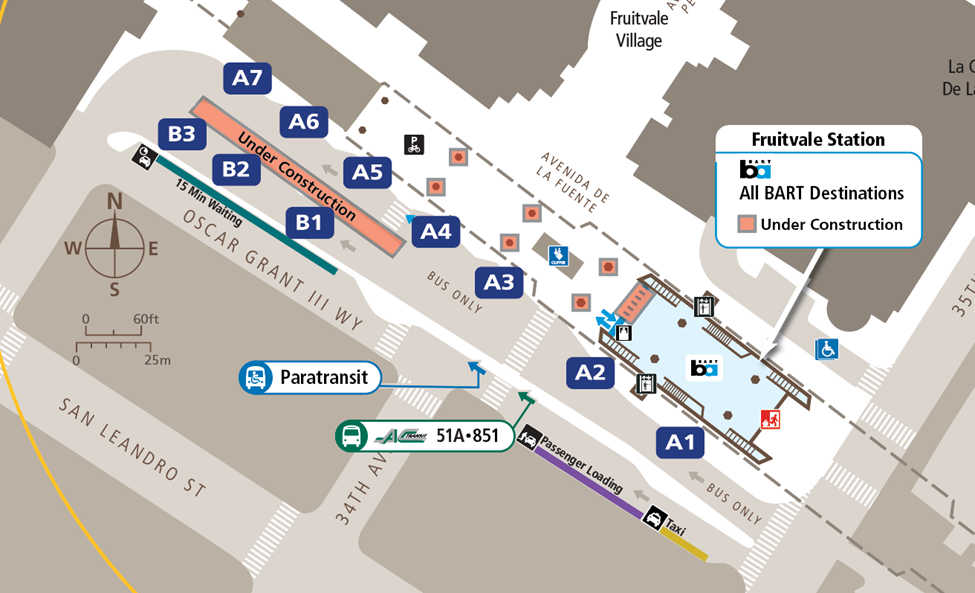

UPDATE: August 28

On Aug 29th, construction in the bus area for the Fruitvale Accessibility Improvement Project will be complete, and buses will return to their normal locations, as shown in the table and first map below using bus stop numbers. Bus stop numbers will also be posted at the bus stops.

Bus stops A1 to A7 are located along the west side of the station, with A1 closest to 35th Ave and A7 closest to the BART garage. Bus stops B1 to B3 are located on the bus island. Signs will be posted at each stop showing the Bus Stop number.

| Bus Line | Bus Stop # |

| 14 | A7 |

| 19 Downtown Oakland | A3 |

| 19 Seminary Ave | A5 |

| 20 Dimond District | A5 |

| 20 Downtown Oakland | A3 |

| 21 Dimond District | A5 |

| 21 Oakland Airport (OAK) | A3 |

| 39 | B2 |

| 51A | A2 |

| 54 | A4 |

| 62 | A6 |

| 648 | B2 |

| 654 | B2 |

| 655 | B2 |

| 703 | A6 |

| 851 | A2 |

| Shuttles | B3 |

UPDATE: August 8

On Aug 9th, the final construction phase of the Fruitvale Accessibility Improvement Project will begin and last for approximately 3 weeks.

Please note: There are two other projects that will take place at the same time at Fruitvale Station:

- New faregates will be installed, for more information see the following news item: https://www.bart.gov/news/articles/2024/news20240801

- And murals will be painted on trackway columns.

During this construction phase the following changes will occur:

The passenger loading zone will move to the left side taxi area, and taxis will move back in the same lane. The diagonal parking to the north of the passenger loading zone will be reserved for 15 Minute Waiting.

Buses will move back into the station area from E. 12th Street and the bus island will remain closed for construction. Temporary bus locations for this phase are shown by Bus Stop number in the second map and table below.

Bus stops A1 to A7 are located along the west side of the station, with A1 closest to 35th Ave and A7 closest to the BART garage. Bus stops B1 to B3 are located on the bus island. Signs will be posted at each stop showing the Bus Stop number.

| AC Transit Line | Bus Stop # |

| 14 | A7 |

| 19 | A3 |

| 20 Dimond | A5 |

| 20 Downtown Oakland | A3 |

| 21 Dimond | A5 |

| 21 Oakland Airport (OAK) | A3 |

| 39 | A2 |

| 51A | Passenger Loading Zone |

| 54 | A4 |

| 62 | A6 |

| 703 | A6 |

| 706 | A4 |

| 851 | Passenger Loading Zone |

Note: the information below was originally published on July 3

Construction for the next phase of the Fruitvale Station Accessibility Improvements Project will begin on Monday, July 8, 2024 and last for approximately six weeks. The first phase will take place from July 8th to July 14th, and the second phase will take place from July 15th to August 9th.

During the first phase, the following temporary changes will occur:

- AC Transit Route 51A and 851 will move to the Passenger Loading Zone

- Passenger Loading will move to the taxi zone on the left side of Oscar Grant Way

- Taxis will move to the southern portion of the zone

During the second phase, the following temporary changes will occur:

- All buses will move to E. 12th Street. Bus lines will be located as follows (see third map below):

| AC Transit Line | Bus Stop |

| 14 | D3 |

| 19 | C6 |

| 20 Dimond | C2 |

| 20 Downtown Oakland | C3 |

| 21 Dimond | C2 |

| 21 Oakland Airport (OAK) | C3 |

| 39 | C1 |

| 51A | C4 |

| 54 | D1,D2 |

| 62 | D4 |

| 706 | D2 |

| 851 | C5 |

Parking: BART parking is typically reserved for riders parking and using BART. However, since parking along E. 12th Street will be removed for buses during this phase, BART is offering non BART riders the ability to park at BART during the closure. Parking is only available in the Daily Fee area on Garage levels 3-5, and the surface lot north of Fruitvale Avenue. Daily Fee parking payment must be made via the BART Official App; payment should be made when the customer parks. . A Clipper Card number is required to buy Daily Fee parking on the app; learn more about how to obtain a free clipper card here: Clipper and Pay by Phone | Bay Area Rapid Transit (bart.gov). Daily Fee parking at Fruitvale is $3.55/day on weekdays and includes the City of Oakland parking tax. Customers who do not pay for parking may be subject to citation. Daily Fee parking is available on a first-come, first-served basis and at your own risk.

Map of Fruitvale parking locations:https://www.bart.gov/sites/default/files/2023-10/BART%20Parking%20Fruitvale.pdf

How to pay for parking on the BART Official App: https://www.bart.gov/guide/parking/payment

As shown in the second map below, to get to the Phase 2 temporary bus locations, exit the station and turn right. Walk through the pedestrian street to E. 12th St.

Bus stops C1 to C3 will be on E. 12th St to the left, C4 and C5 will be on the right.

Bus stops D1 and D2 will be on the opposite side of E.12th St to the left, and D3 to D5 will be to the right.

This construction is part of the Accessibility Improvement Program (AIP), which improves accessibility in and around BART stations to better meet the needs of people with disabilities, including replacement or upgrade of ramps, sidewalks and accessible paths, bus and passenger loading zones, as well as handrails, wall protrusion detection, wheelchair-accessible phones, TTY devices, courtesy phones, and elevator lobby lighting.